Fyodor gripped the envelope in a bird-like fist and stared into the fire. They would be coming now, soon: the telephone calls from family and friends he had not spoken to in years, hoping to make up for past abandonments by being first in line. Reporters. He looked at the pitiable mound of pink slips on his desk, bills that taunted, threatened, and ruled him only a few days ago, and he felt with a horrible sinking in his chest that they had no power over him any more.

Six months ago everything had been different. First, his wife’s affair, well-documented by the local press, became so messy and sensational that his supervisor had been forced to fire him. The shock of losing his wife and his livelihood all at once caused him to begin having panic attacks again, after which even those who remained by him after the scandal were too embarrassed to accompany him in public.

He had been, in a word, miserable. He never left his apartment, which began to smell like the home of someone who had recently died and whose corpse had not been found. Eventually he pulled out a novel he had started writing shortly after getting married, and occupied himself by making revisions. He crossed out more than he added. Whole sheets crinkled and disappeared in the fire. These small acts of destruction buoyed him, gave him hope, but there was soon little left to destroy – and so he began to write, long uneven pages of it, a writing that was as violent as the destruction had been.

He prayed, yes, he prayed that the book would lead him out, he prayed to the book, for it was all that was left to him, a hope of thinnest glass. Oh, but that he could feel happiness once again before his days ran out! He did not know if it was possible.

But the curious thing about memory is that it has no capacity for pain. One can remember times of suffering, of course, but try as one might one will not conjure the feeling of suffering itself, the claustrophobia and the terror: these are gifts that leave you when you leave them. And so it went that Fyodor pulled himself together, he scraped by with a night shift at a gas station, cut his hair, began – once more – to hum. One night he saw a pair of squirrels perching silently on a branch, their small faces toward the light of the full moon, and he remarked how curious it was. And then he got the letter.

He wanted, now, desperately to turn back the clock, to go back a few days before he had read the news, to a time when everything was gloriously uncertain. Yes, he had been doing better, but he never deluded himself that he was in the clear, that – as the stories go – he would live happily ever after. Then, the world could still have ended. Now the world sided annoyingly with him, giving him exactly what he had asked for, all of it, and it made him sick to think about.

And then he thought, what if this is a sign that I am not yet happy? What if my feeling sick means that I am not actually there, but that just the outward conditions that I always assumed led to happiness have been fulfilled? For now the curtain is raised, there is no escaping the truth anymore: where before I could have blamed my lack of happiness on a lack of things, I now lack no more and yet still feel a lack. I cannot live in the charade any more. I have done all that I can, and yet I still lack.

And with this thought relief rushed through him like fresh rain.

Friday, January 29, 2010

Monday, January 18, 2010

China, a start

A lot of people know a little bit about China's one-child policy, which I learned today has been in place since 1979 and will likely remain for at least the next ten years. If you know as little about this as I did a few hours ago (and I only know a very little more now), I might ask you to stop with me before we go further and agree that we ought not to be looking for an equivocal stance on whether the policy is good or not – a discussion which always seems to implicate China as a whole, as if our opinion of the regulation of family sizes would indicate an opinion of China as either a practical, prosperous economic engine or as a faceless government-controlled land bereft of basic human rights. Issues that are this complicated do not have on/off switches for answers, and there may not exist a single person anywhere who understands the history and circumstances of the issue well enough to make a judgment that approximates something like objectivity. All we can do – all we can ever do – is learn as much as we can, and remember that our own understanding is always partial. Only then will we be open to others' partial understandings and more reasonable in our suggestions of what might be done.

The Wikipedia entry on the one-child policy is a good start, and led me to one article that seems an example of What Not To Do. It’s a petition published ten years ago in the Washington Times that aims to browbeat its readers into adopting the author’s rather extreme views, and thereby attempts to prevent the funding of population control programs like China’s family planning policy. Many of the points raised by the author – such as the very real problems concerning the favouring of sons over daughters, a cultural proclivity which results in a staggering imbalance in the gender ratio, something like 120-100 nationwide – have also been raised by other, more even-handed writers, but the present author mixes in what might be truth with such obviously militant pronouncements and rhetoric that it’s hard to take him seriously. It is of course a good thing that many will be introduced to the subject through this article, and will hopefully be motivated to read further and think for themselves, but the corollary danger is that the real injustices and crimes mentioned, the rates of infanticide and the cultural bias against girls, may be dismissed by readers who object to the writer’s caustic, bullish prose.

Stephen Moore (the author) writes that “no sane person” would subscribe to the view he objects to, which, if you think about it, is sort of just a mild way of saying “you’re all crazy.” It’s not a long stretch from this to the adjectives he appends to any mention of the fund or the family planning policy, which include “genocidal,” “fanatical,” and “demon-like.” With the exception of “genocidal,” which is a real and serious accusation, the language Moore employs is emotional and imprecise, and doesn’t tell us very much. I always think in situations like this: if this person thinks a system is “fanatical,” there must be one other person who thinks it isn’t, and wouldn’t it be nice if I had a glimpse of the opposing argument to compare? But Moore’s article is staunch and impenetrable.

I don’t want to turn this in to a catalogue of all the pros and cons of family planning in countries such as China, because I don’t know enough on the subject and don’t pretend to. That being said, I know enough already to raise my eyebrows when Moore writes that

I will only say one more thing here, which is that Moore’s own solution to the problem seems to be that we ought to inject more capitalism into China and watch as it solves everything. This is evident even before his last paragraph, in which he basically says that all Third World countries should model themselves after the U.S. in order to improve themselves. I won’t address Moore’s contentions directly, except to say that when the problem is as complex and variegated as this one is, in a country as large and politically bristly as China, and your solution is a one-liner combined with a dismissal of all the cultural, economic, social and historical realities that underscore the daily lives of nearly a billion and a half people - well, your solution may not get us very far.

The Wikipedia entry on the one-child policy is a good start, and led me to one article that seems an example of What Not To Do. It’s a petition published ten years ago in the Washington Times that aims to browbeat its readers into adopting the author’s rather extreme views, and thereby attempts to prevent the funding of population control programs like China’s family planning policy. Many of the points raised by the author – such as the very real problems concerning the favouring of sons over daughters, a cultural proclivity which results in a staggering imbalance in the gender ratio, something like 120-100 nationwide – have also been raised by other, more even-handed writers, but the present author mixes in what might be truth with such obviously militant pronouncements and rhetoric that it’s hard to take him seriously. It is of course a good thing that many will be introduced to the subject through this article, and will hopefully be motivated to read further and think for themselves, but the corollary danger is that the real injustices and crimes mentioned, the rates of infanticide and the cultural bias against girls, may be dismissed by readers who object to the writer’s caustic, bullish prose.

Stephen Moore (the author) writes that “no sane person” would subscribe to the view he objects to, which, if you think about it, is sort of just a mild way of saying “you’re all crazy.” It’s not a long stretch from this to the adjectives he appends to any mention of the fund or the family planning policy, which include “genocidal,” “fanatical,” and “demon-like.” With the exception of “genocidal,” which is a real and serious accusation, the language Moore employs is emotional and imprecise, and doesn’t tell us very much. I always think in situations like this: if this person thinks a system is “fanatical,” there must be one other person who thinks it isn’t, and wouldn’t it be nice if I had a glimpse of the opposing argument to compare? But Moore’s article is staunch and impenetrable.

I don’t want to turn this in to a catalogue of all the pros and cons of family planning in countries such as China, because I don’t know enough on the subject and don’t pretend to. That being said, I know enough already to raise my eyebrows when Moore writes that

family planning services do not promote women's and children's health; they come at its expense. There are many Third World hospitals that lack bandages, needles and basic medicines but are filled to the brim with boxes of condoms -- stamped UNFPA or USAID.It’s not clear how the lack of resources in third world hospitals is related to the promotion of smaller families, but I would think that increasing the number of births in such hospitals would not in itself lead to better all-round sanitation. I also don’t see the connection to condoms, which are freely distributed in clinics in many other countries, including in the west. Contraception, whose purpose is to curtail unwanted pregnancies, is surely good sense and has nothing to do with the ability of couples to control the number of offspring they have, except perhaps to improve it. Moore thus makes a false monster (or a straw man) out of a population-control initiative that I can’t imagine anyone objecting to: that of reducing the number of unplanned, accidental and unwanted pregnancies in a population already bursting at the seams.

I will only say one more thing here, which is that Moore’s own solution to the problem seems to be that we ought to inject more capitalism into China and watch as it solves everything. This is evident even before his last paragraph, in which he basically says that all Third World countries should model themselves after the U.S. in order to improve themselves. I won’t address Moore’s contentions directly, except to say that when the problem is as complex and variegated as this one is, in a country as large and politically bristly as China, and your solution is a one-liner combined with a dismissal of all the cultural, economic, social and historical realities that underscore the daily lives of nearly a billion and a half people - well, your solution may not get us very far.

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Not much to ask

I'll try to reveal as little as I can. I recently watched a certain movie about which I knew very little, except that it was considered by some to be the best film of the last decade. My lack of knowledge was deliberate, as it always is with movies I know I will watch, but as I loaded the movie on my computer I accidentally read the one-line "summary" that ran under the video window. Normally, this wouldn't be a problem - except in this case that one line provided information not known to the viewer until the very end of the movie, information that, when known, changes the experience of watching the first 90% of the movie dramatically and irrevocably.

But hey, we live in a film culture where "the element of surprise," as they say, is battered and beaten into a corner. Even if you don't read reviews or watch trailers online (both of which I do), it is nearly impossible to avoid promotional posters, TV spots, trailers played before movies. These can ruin a lot more than people seem to realize. Take the poster for Antichrist, which features one of the most striking, surprising and terrifying images in the movie, that of hands reaching out of the roots of a large tree toward the two characters, having sex. If you were at all interested in this movie, you will have seen this picture, which means that nearly no one experienced this scene in the movie as a discovery, as the uncovering of something strange and new.

Because surprises are not only plot surprises, and surprises in film are not the same as surprises in life. Film is, after all, a medium built on images, and images can be some of the most surprising things that movies offer us. Put another way: one of the most important things movies give us is new images, in the same way that new music can give us sounds that never existed before. Art creates new realities that are added to our collective repertory, so that the entirety of the world becomes richer for it. When you see an image for the first time, it offers its secret to you; later viewings of the same can still be powerful, but only the first viewing is like discovery, has the thrill of fear and the sense of some illicit transaction being made.

If you hold a surprise party for me and I find out about your plans, it doesn't mean I won't go because the surprise is ruined. Rather, I go because the pleasure and shock of my friends gathered together for me is still meaningful, in a way that the loss of surprise does not diminish. Surprise in life is only the mode of communication; it does not make less the substance of surprise, the party, the baby announcement, the loss of job. But film is no more and no less than a mode of communication - it's "how it's told," as people like to say. The surprise itself is the content of the surprise.

Why is it so important to defend our right to be surprised? I think back to all the moments I remember vividly from films, and they all combine powerful scenes with surprise. Somehow the surprise part is crucial. After all, it wouldn't do for us to walk around our houses, being surprised at everything. Surprise is the recognition that something different has just happened, and we need to pay attention. It is when our focus is at its most acute, and our memory like blank film stock, waiting for the light to hit. It makes us the best possible receiver for new thoughts.

This is what I want, or more precisely, what I don't want: I don't want to see any scene, any image, from the film. I don't want to know who the director is or which actors are in it. Hell, I don't want to know if it's comedy or a thriller or drama. I just watched Vicky Christina Barcelona and somehow forgot that Penelope Cruz is in it, and when she stormed in halfway through I almost fell out of my chair. Surprise is a good thing, and worth fighting for.

But hey, we live in a film culture where "the element of surprise," as they say, is battered and beaten into a corner. Even if you don't read reviews or watch trailers online (both of which I do), it is nearly impossible to avoid promotional posters, TV spots, trailers played before movies. These can ruin a lot more than people seem to realize. Take the poster for Antichrist, which features one of the most striking, surprising and terrifying images in the movie, that of hands reaching out of the roots of a large tree toward the two characters, having sex. If you were at all interested in this movie, you will have seen this picture, which means that nearly no one experienced this scene in the movie as a discovery, as the uncovering of something strange and new.

Because surprises are not only plot surprises, and surprises in film are not the same as surprises in life. Film is, after all, a medium built on images, and images can be some of the most surprising things that movies offer us. Put another way: one of the most important things movies give us is new images, in the same way that new music can give us sounds that never existed before. Art creates new realities that are added to our collective repertory, so that the entirety of the world becomes richer for it. When you see an image for the first time, it offers its secret to you; later viewings of the same can still be powerful, but only the first viewing is like discovery, has the thrill of fear and the sense of some illicit transaction being made.

If you hold a surprise party for me and I find out about your plans, it doesn't mean I won't go because the surprise is ruined. Rather, I go because the pleasure and shock of my friends gathered together for me is still meaningful, in a way that the loss of surprise does not diminish. Surprise in life is only the mode of communication; it does not make less the substance of surprise, the party, the baby announcement, the loss of job. But film is no more and no less than a mode of communication - it's "how it's told," as people like to say. The surprise itself is the content of the surprise.

Why is it so important to defend our right to be surprised? I think back to all the moments I remember vividly from films, and they all combine powerful scenes with surprise. Somehow the surprise part is crucial. After all, it wouldn't do for us to walk around our houses, being surprised at everything. Surprise is the recognition that something different has just happened, and we need to pay attention. It is when our focus is at its most acute, and our memory like blank film stock, waiting for the light to hit. It makes us the best possible receiver for new thoughts.

This is what I want, or more precisely, what I don't want: I don't want to see any scene, any image, from the film. I don't want to know who the director is or which actors are in it. Hell, I don't want to know if it's comedy or a thriller or drama. I just watched Vicky Christina Barcelona and somehow forgot that Penelope Cruz is in it, and when she stormed in halfway through I almost fell out of my chair. Surprise is a good thing, and worth fighting for.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

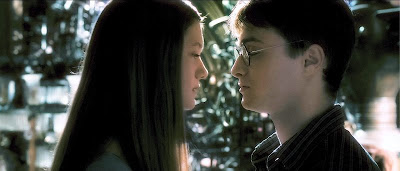

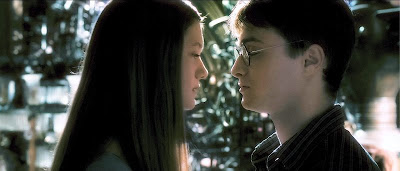

Rewatching Half-Blood Prince

The first time I saw Half-Blood Prince in the summer I was prepared to dislike it. It was directed by David Yates, whose Order of the Phoenix did something worse than leave a bad impression on me - it left no impression at all. I can't now recall a single scene from that movie, which makes you wonder what the purpose is of making film versions of Harry Potter in the first place - or, to rephrase, Why do we watch these movies? But I'll get to purpose later. Let's consider Half-Blood Prince first.

It must be hard to follow Alfonso Cuaron, I kept thinking to myself. That man understood. In 6, Harry looks positively astounded as Dumbledore cleans up Slughorn's house with a flick of his wand - really? After six years? You're still bowled over by a clean-up charm?

Compare with Azkaban, which has the most subtle, unfussy touches of magic, sometimes presented in such banal fashion that you catch them only on a second viewing. I remember noticing, as I watched the movie a second time, that the barman in the Leaky Cauldron waves his hand at the chairs and doesn't even pay heed as they raise themselves up and tuck themselves neatly in. It's an astounding piece of CGI that isn't given a second thought. Magic, of course, is commonplace for those on-screen, and that is what makes it so special for us, that something so alien to us could be so boring in their world. By contrast, Yates is like a kid showing off his lunch Twinkies, making sure the camera zooms in on every bit of lame magic and every visual gag, so that what might have been charming or whimsical if left at the periphery becomes overburdened and even a little embarrassing.

My sense is also that the actors don't feel quite as comfortable working with Yates as they did with any of the previous directors. There are so many scenes dependent on dialog that fall utterly flat; scenes that should end with a rise, as with a good punchline, instead feel horribly dead, end with a leaden awkwardness. Yet there are some really wonderful exceptions, such as all the moments having to do with the Hermione-Ron-Cormac love triangle: watch Hermione as she picks up the love potion in Slughorn's class, looks at Cormac, and puts the bottle back. I don't think she's ever acted better.

And I must mention as well my favourite scene in the movie, which is not in the book. It's when Slughorn tells the story of the petal in the bowl of water that Lily gave him as a gift, which sank to the bottom and transformed into a tiny fish. "It was beautiful magic, wondrous magic," he says, his eyes lost in the past. The existence of this scene is what saves the movie from being dispensable; it gives us something of Slughorn and, more importantly, of Lily, that the books don't.

And I must mention as well my favourite scene in the movie, which is not in the book. It's when Slughorn tells the story of the petal in the bowl of water that Lily gave him as a gift, which sank to the bottom and transformed into a tiny fish. "It was beautiful magic, wondrous magic," he says, his eyes lost in the past. The existence of this scene is what saves the movie from being dispensable; it gives us something of Slughorn and, more importantly, of Lily, that the books don't.

But why does there have to be so much garbage in there too? Like the movie Ginny, who is so over-sexed the character most similar to her on screen is Bellatrix Lestrange - and that's a problem. Yes, Ginny grows older and more confident, and a part of that is a bloom in sexuality, but there is also a component of character in the book, in which Ginny defends her actions to a jealous Ron and manages irony when she comes across the same snogging Lavender. In the movie the sex sprouts ahead and the character is left behind, so that she seems little more than a whore - or a "scarlet woman," as Molly would put it.

But we could go on all night like this, exchanging checks and crosses. It all comes to down this question: why, when we already have read and loved the books, do we go to the movie? There are a lot of simplistic and snide answers to this, but I still think it's worth asking. What, exactly, are we looking for? The movie will never be as "authentic" as the book, so we are not looking for authenticity, which means that the movie should feel free to veer from the material and surprise us.

But we could go on all night like this, exchanging checks and crosses. It all comes to down this question: why, when we already have read and loved the books, do we go to the movie? There are a lot of simplistic and snide answers to this, but I still think it's worth asking. What, exactly, are we looking for? The movie will never be as "authentic" as the book, so we are not looking for authenticity, which means that the movie should feel free to veer from the material and surprise us.

I think about some of the moments in the movies that have stuck with me - Slughorn's memory of Lily, the moment in 4 when Neville gathers his courage and steps forward, first to dance - these have given me emotional jolts that live alongside those I've gotten from reading the books. The greatest weakness of the last two movies has been their reliability, because their reliability has made them forgettable. What might, might give them reason to exist is what newness they have to offer us, what moment or shot that is expressed better than we could conceive of it ourselves. We should be looking for sensory experiences that amplify our experience of reading, that give texture and substance and sound to the solitary act of imagination.

It must be hard to follow Alfonso Cuaron, I kept thinking to myself. That man understood. In 6, Harry looks positively astounded as Dumbledore cleans up Slughorn's house with a flick of his wand - really? After six years? You're still bowled over by a clean-up charm?

Compare with Azkaban, which has the most subtle, unfussy touches of magic, sometimes presented in such banal fashion that you catch them only on a second viewing. I remember noticing, as I watched the movie a second time, that the barman in the Leaky Cauldron waves his hand at the chairs and doesn't even pay heed as they raise themselves up and tuck themselves neatly in. It's an astounding piece of CGI that isn't given a second thought. Magic, of course, is commonplace for those on-screen, and that is what makes it so special for us, that something so alien to us could be so boring in their world. By contrast, Yates is like a kid showing off his lunch Twinkies, making sure the camera zooms in on every bit of lame magic and every visual gag, so that what might have been charming or whimsical if left at the periphery becomes overburdened and even a little embarrassing.

My sense is also that the actors don't feel quite as comfortable working with Yates as they did with any of the previous directors. There are so many scenes dependent on dialog that fall utterly flat; scenes that should end with a rise, as with a good punchline, instead feel horribly dead, end with a leaden awkwardness. Yet there are some really wonderful exceptions, such as all the moments having to do with the Hermione-Ron-Cormac love triangle: watch Hermione as she picks up the love potion in Slughorn's class, looks at Cormac, and puts the bottle back. I don't think she's ever acted better.

And I must mention as well my favourite scene in the movie, which is not in the book. It's when Slughorn tells the story of the petal in the bowl of water that Lily gave him as a gift, which sank to the bottom and transformed into a tiny fish. "It was beautiful magic, wondrous magic," he says, his eyes lost in the past. The existence of this scene is what saves the movie from being dispensable; it gives us something of Slughorn and, more importantly, of Lily, that the books don't.

And I must mention as well my favourite scene in the movie, which is not in the book. It's when Slughorn tells the story of the petal in the bowl of water that Lily gave him as a gift, which sank to the bottom and transformed into a tiny fish. "It was beautiful magic, wondrous magic," he says, his eyes lost in the past. The existence of this scene is what saves the movie from being dispensable; it gives us something of Slughorn and, more importantly, of Lily, that the books don't.But why does there have to be so much garbage in there too? Like the movie Ginny, who is so over-sexed the character most similar to her on screen is Bellatrix Lestrange - and that's a problem. Yes, Ginny grows older and more confident, and a part of that is a bloom in sexuality, but there is also a component of character in the book, in which Ginny defends her actions to a jealous Ron and manages irony when she comes across the same snogging Lavender. In the movie the sex sprouts ahead and the character is left behind, so that she seems little more than a whore - or a "scarlet woman," as Molly would put it.

But we could go on all night like this, exchanging checks and crosses. It all comes to down this question: why, when we already have read and loved the books, do we go to the movie? There are a lot of simplistic and snide answers to this, but I still think it's worth asking. What, exactly, are we looking for? The movie will never be as "authentic" as the book, so we are not looking for authenticity, which means that the movie should feel free to veer from the material and surprise us.

But we could go on all night like this, exchanging checks and crosses. It all comes to down this question: why, when we already have read and loved the books, do we go to the movie? There are a lot of simplistic and snide answers to this, but I still think it's worth asking. What, exactly, are we looking for? The movie will never be as "authentic" as the book, so we are not looking for authenticity, which means that the movie should feel free to veer from the material and surprise us.I think about some of the moments in the movies that have stuck with me - Slughorn's memory of Lily, the moment in 4 when Neville gathers his courage and steps forward, first to dance - these have given me emotional jolts that live alongside those I've gotten from reading the books. The greatest weakness of the last two movies has been their reliability, because their reliability has made them forgettable. What might, might give them reason to exist is what newness they have to offer us, what moment or shot that is expressed better than we could conceive of it ourselves. We should be looking for sensory experiences that amplify our experience of reading, that give texture and substance and sound to the solitary act of imagination.

Friday, January 1, 2010

The sound and the sublime

The first image in Lars von Trier's Antichrist is of falling droplets of water. The second is the shot of Willem Dafoe, above, and what you can't entirely see is the shower of droplets that fill the right side of the screen, here left out. Even without the droplets, though, my sense is that the picture above points downward; there is something directional in the gravity of the composition, maybe the downward drooping left eye or the shadow that gains along the underside of his chin.

The first image in Lars von Trier's Antichrist is of falling droplets of water. The second is the shot of Willem Dafoe, above, and what you can't entirely see is the shower of droplets that fill the right side of the screen, here left out. Even without the droplets, though, my sense is that the picture above points downward; there is something directional in the gravity of the composition, maybe the downward drooping left eye or the shadow that gains along the underside of his chin.And so the opening sequence of Antichrist is full of the imagery of falling, which makes sense for a film about original sin. Toothbrushes and cups are knocked over, figurines are swept off the table, snow drifts down and bodies fall to the floor, all of which surround the fall of Nic from his bedroom window. And a shot I find almost unbearably poetic: that of Nic's feet reaching slowly to the ground as he climbs out of his crib, the white stars on the bottoms of his socks visible, a reversal of heaven and earth.

After the prologue, things keep falling. The beautifully filmed white bathroom where the couple makes love is now a dirty, wan place where Charlotte Gainsbourgh crawls and bleeds. And in Eden, nature quite literally falls all around them, from the acorns that pelt their cabin to the trees and birds that simply fall out of the sky. Underscoring all of these events is a kind of aesthetic fall, from the beauty and light of the opening sequence to the brutal sexual violence that turned so many viewers away. It is a far, far drop from Handel and droplets of water to some of the places Lars von Trier takes us in the second half of the film.

I believe this is why the epilogue is so effective, set to the same Handel as the beginning but now working against the dogged downward gaze of the rest of the film, working against the gravity that had been tugging down at the edges of the screen. The Nature of stillbirths and violence and hostility, of twisted tree trunks and dark forests, is now again a benevolent Nature, one that offers Dafoe sustenance through its berries. We, with Dafoe, rise out of the pit, and then comes the image that sets our sense of aesthetic balance right - first a few, then more, then a migration of women rising up a hill, climbing the slope where Dafoe stands and moving on past the upper edge of the screen. Fall, fall, fall, and then a reversal at the end: the simple and tremendously moving form of Antichrist.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)